For someone with a long career in ICT, it’s always a bit uncanny to hear about the trending notion of “Digital Transformation”. While Information and Communication Technologies strictly speaking have their roots in century-long analog technologies, the concept as we know it is often perceived as synonymous with “digital”, and its transformational powers were crystal clear already in the past century, see e.g. the Information Age trilogy by Manuel Castells. So nothing really new there. Or is it?

The birth of Adonis and the transformation of Myrrha. Oil painting by Luigi Garzi. Welcome collection, CC-BY

Let’s try to understand what this “transformation” really could mean. I would like to propose an example: when universities introduced the now very common Learning Content Management Systems at the start of the current millennium, it was originally a question of setting up a server that ran an online application. Often it was implemented completely separated from other university management systems, with a different set of logins, and mostly at the department or faculty level. Many Faculties had their WebCT, Blackboard, or Moodle-based server. Originally, it consisted mostly of a delivery system for digitized course contents, e.g. in PDF format. Gradually, however, functionalities were added to make it more of a comprehensive “Virtual Learning Environment“, where learning activities such as exercises and tasks could be done online.

The transformational impact of ICT

At KU Leuven, we soon realized that another approach was needed: not only was it not very smart to manage such a system independently from other university management systems, but it also became clear that given education, including teaching and learning activities, is a core pillar of the university business, the VLE should be integrated into the core architecture of our ICT systems. In fact, we needed to develop at the university the specific ICT solutions to support and deliver our main educational outputs.

While originally the drive, motivation, and requirements for the VLE came from pedagogy, a radical shift was needed, and we needed to put ICT in the pilot seat. In fact, we realized that the whole teaching and learning activity was still beyond the radar of our information processes. The real digital “transformation” would be to capture what was happening in the classrooms and study centres as an information stream, which would help us to manage, control, and optimize these processes. Suddenly, the analytics information from the LCMS became a very important source material to base our policy actions on. This insight was not readily adopted by the education management boards in the Faculties or at the university level, and we quickly learned that it was safer to just do it and implement it than to talk too much about it. Looking at education from the viewpoint of Claude Shannon’s information theory was a bit eery, but just plain logical.

Inside-out and outside-in

15 years later it is generally accepted that “Digital Transformation” – or the implementation of impactful ICT infrastructures – implies rethinking the core business processes and organizational workflows. This is what is happening today in the Cultural Heritage / GLAM sector. People look beyond the digital catalog or website portal to understand they need a coherent digital strategy to make sure their business processes and services are based on their information exchange systems. It is important to note, however, that up to now, IMHO, implementations of digital strategies in the GLAM sector have failed to understand the real importance and opportunities of “going digital”. Most implementation models are still mainly “inside-out”. They focus on the collections and how to push them to the outside users. The idea is that “Open Access” would benefit the user communities somehow, with a long tail model, involving a majority of users just consulting and browsing the materials, and a more dedicated segment really taking advantage of this source material to create new outputs. Open Access policies are a generally accepted ingredient of CHI policies, for good reason. But then again: they look at publishing digitized collections from an inside-out perspective.

From a more generic view on online publishing and website development, I would say that this is not the way to go. One of the main things that I want students in my class on Online Publishing to understand, is that for a website, it is as important to get information in than to get information out. In fact, pushing information out requires a lot of effort, maintenance, and cost. The real gain is what you get back: the information that comes in from the use of your website. This is, of course, the basis of any website built for commercial purposes – a restaurant publishes its website to get reservations in the first place. It is also the business model that lies at the core of big distribution platforms such as Amazon and the likes, where the added value is the knowledge that they glean from users of all parts of the value chain while using these portals.

And yet, this essential insight, that the information coming in is the main reason why you would make the effort to push information out, seems often lost when thinking about publishing digital collections in the GLAM sector.

Rethinking Open Access

The idea is that when we segment the more active part of this user community, we will see that there are intensive amateur users, an intermediate category dubbed the ” pro-ams” and then a more professional community who would turn this raw material into new products and services, in other words, the “creative industries”. It is difficult to assess the true impact and scale of this creative reuse in the GLAM sector, but I am confident good examples exist, and we are gathering them on the participatory platform of our Indices H2020 project.

We should think about what we aim for when people have access to our digital collections. What is the real potential? We seem to be lacking a vision about what “reuse” could mean in the context of heritage. I guess we all understand “reuse” as a secondary use, beyond the primary, private individual use. Let’s not forget that also the primary use has a long tail structure: there are communities who use the contents of digital collections in a casual, ephemeral way: “looking around” a bit or coming in on your portal in search for one piece of information. But there are the more passionate culture lovers who spend many, many hours studying the digital collections. In the end, there are professionals who actually need this content to integrate it into their work. In the case of cultural heritage collections, teachers, educators, and researchers come to mind. And fellow CHI colleagues who are looking for missing pieces, or want to build a virtual overview of dispersed collections. Once a new result, product or service comes out of this primary use we call it “reuse”. That could be a gallery, a story, a game, or an app. Open Access, exemplified by OpenGLAM is then the publishing of digital collections in such a way that people have the license to reuse this content.

Curation beyond patronage

However, this model still sees the cultural heritage institution as the guardian of the heritage collections. It leaves the basic mission of the institution untouched: to safeguard, preserve, and select what is to be considered as heritage. Pier Luigi Sacco calls this the “Culture 2.0” model. And in fact, it is a commodification of heritage. It doesn’t question what actually makes objects from the past “heritage”. Is it merely “inheritance”? Getting stuck with loads of old stuff? We would say no: it is the result of selection, curation, and canonization of what has been deemed “valuable”. Up until the end of the 20th century, we left selection, curation, and canonization in the hands of professionals from the GLAM institutions and scholars. Not only did they have privileged access, but they also are supposed to have the necessary knowledge to make the right judgments.

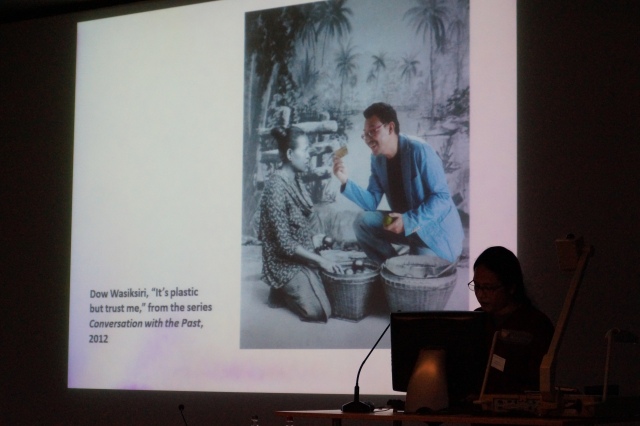

The Open Access movement wants to change this. It wants to open up collections through digital technologies to allow broader audiences to have access to even the most vulnerable heritage, by means of mass digitization and open licensing. To make this access meaningful and useful, we are moving from a catalog style record, listing some summary data about the objects, to ever richer, multilingual metadata – more and more automatically enhanced through deep learning algorithms – and more sophisticated digital representations such as 3D, multispectral imaging and OCR, so that users can access and engage with the true properties of the digitized objects.

But should the buck stop here? Is this the participatory Culture 3.0 paradigm shift Pier Luigi Sacco is talking about? We are trying to find out in the Indices project, which aims to understand how Open Access can form part of the core workflows and business models in GLAM and Cultural Heritage institutions to really take advantage of what ICT can bring to the table.

Users can do so much more than just browse through some content and download images. They can contextualize the content from their own lived experience. They can assist in co-curation, tagging, translations, transcription efforts. More importantly, they can connect the collection objects to their natural habitat, which is not the gallery, library archive, or museum but the cultural community which gives meaning and symbolic value to those objects.

So the ICT tools we should be looking at are not only the digitization, distribution, and visualization tools. It should include the participatory platforms that allow people to engage with the contents, to start commenting, selecting, curation, and co-creating stories. To start informed debates about the values that the collection objects represent. A clear example of this shift is the way communities want a say in how colonial-era content can be re-represented and “decolonized”. While the actual composition of European society has dramatically changed since the 20th Century, the collections in European GLAM institutions, the metadata descriptions, and the narratives in which they are embedded have failed to reflect this. Communities that are now in the inside of European history, are often portrayed as belonging to outside worlds. We badly need new, inclusive narratives that give more sustainable meaning and value to heritage collections.

In conclusion

Let’s take the next step in Open Access, and start to share digitized cultural heritage collections in a way that enables communities to not only to co-curate and co-create content, but also gives them a voice to co-decide what we consider heritage, how we assess its value, how we can make it more representative for past, current and future audiences. New generations of Europeans are ready to take on this task – the “citizen science” for the GLAM sector so to say – they are virtually knocking on the door of our institutions. let’s let them in. That would be truly Open Access.

The transformation of Myrrha gave birth to Adonis according to Greek mythology. Let’s see what beautiful offspring the digital transformation will bring to Cultural Heritage!

The E-Space Education portal highlights the results of the pilots and demonstrators, and gives clues how these outputs can be used in educational contexts. However, if you really want to learn how to do this, you need some more concentrated effort! This is why we decided to offer a MOOC, hosted on the

The E-Space Education portal highlights the results of the pilots and demonstrators, and gives clues how these outputs can be used in educational contexts. However, if you really want to learn how to do this, you need some more concentrated effort! This is why we decided to offer a MOOC, hosted on the

You must be logged in to post a comment.